THE BIG SCREEN: Historic Psychedelia, Animation, and Avant-Garde Films in Large Format

The Plaza Theatre

May 29, 2025

Curated by Andy Ditzler and Gregory Zinman

The Dante Quartet (Stan Brakhage, 1987) 6 min projected in 35mm

Spirochaeta Pallida (Agent de la Syphilis) (Jean Comandon, 1909) 4 min

Synchromy No. 2 (Mary Ellen Bute, 1936) 6 min

Our Lady of the Sphere (Lawrence Jordan, 1969) 10 min projected in 35mm

Calculated Movements (Larry Cuba, 1985) 6.5 min

Robert Abel Promo Reel (Robert Abel and Associates, 1970s) 8 min

Passage a l’Acte (Martin Arnold, 1989) 12 min

Mirror (Matthias Müller and Christoph Girardet, 2003) 8 min projected in 35mm Cinemascope

Synchromy (Norman McLaren, 1971) 8 min

Garden of Earthly Delights (Stan Brakhage, 1981) 3 min projected in 35mm

Program notes:

Cinema’s smaller formats – 16mm film, 8mm and Super-8mm, VHS tapes, camera phones – have for many reasons traditionally been the choice for experimental and avant-garde filmmakers. But occasionally – and in quite varying circumstances – film artists have worked in larger, industrial-sized formats. Tonight’s selections each come at the large-format medium from different angles, but all are concerned with new visions, visions that foreground the extant technology of the moving image even as they suggest different, heretofore unseen cinemas.

These ten films speak to each other in different ways. There’s materiality: Stan Brakhage’s paint directly on the filmstrip, Norman McLaren hand-printing his musical score directly on the soundtrack strip, Martin Arnold cutting a scene from To Kill a Mockingbird down to its individual frames, Brakhage pasting vegetation on the film strip to create a literal garden onscreen, or Jean Comandon’s images of tiny syphilis cells inside a cornea – the material nature of the human body, through the material of film. Then there’s the tension between representation – that is, film as a photographic record of something in the world – and abstraction, or images that (seem to) refer to nothing outside themselves. There are the attempts by filmmakers to merge the separate senses of hearing and vision, or as one put it, “the eye hears and the ear sees.” There’s the longstanding mutual attraction, not without conflict, between mainstream cinema and the avant-garde. And there’s the idea, always fascinating to us, of what constitutes cinema. A 1909 film of syphilis cells – is that cinema? (Why not?)

It’s certainly experimental cinema, on a couple of different levels. Which brings us to a final point. “Experimental,” “avant-garde” – these are loaded terms, right? For some, intimidating or off-putting or obtuse or just plain weird. But if we’re open to the experience, experimental films teach us new ways to see and hear the world, with pleasure always on the table. So let us say this: Besides the large-format theme, our one overriding question when considering a film for this program was: will it blow your minds? We hope you take pleasure in these films – these visions are so worth your time.

The Dante Quartet (Stan Brakhage, 1987) 6 min projected in 35mm

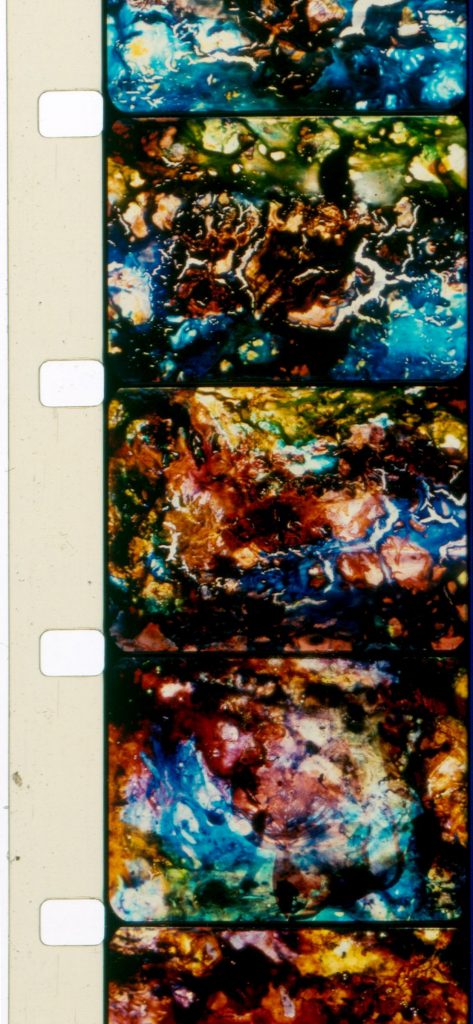

We begin with Stan Brakhage’s The Dante Quartet, shown here in a 35mm print. Brakhage painted these images directly onto IMAX film, 70mm film, and 35mm film, mostly painting over footage from other films (including a print of his own film Garden of Earthly Delights, which concludes tonight’s program). As with so many Brakhage films, the printing lab, Western Cine, and its technician Sam Bush, were instrumental in the creation of The Dante Quartet’s final, four-part form. In his painting, Brakhage seems to have disregarded framelines and to have used the length of the entire film strip as a complete canvas. It was up to the printing process to separate Brakhage’s torrential imagery into discrete frames so that it could be projected as a coherent moving image work. Many have tried to describe the resulting flood of rhythm and color with words like our “torrential” above. But though Brakhage’s inspiration for the film was a literary work, it is difficult to translate this film into language without diminishing it. It’s an experience – as Adrian Danks has written, “a range, depth and density of imagery seldom experienced in or created by the cinema.” Instead of using the moving image to impart information or tell a story, The Dante Quartet provides an experience of seeing, or in Brakhage’s telling, “an adventure of perception.”

Spirochaeta Pallida (Agent de la Syphilis) (Jean Comandon, 1909) 4 min

In their own way, each of these films stretches the motion picture apparatus to one or another of its limits. Around 1909, the French medical researcher Jean Comandon, who was investigating the disease of syphilis, discovered a way to photograph the motion of bacteria cells under a microscope. The resulting film, digitized from a copy in the French national film archive and seen here in its entirety, was an important moment in the history of medical research, but it also represented a new kind of vision through technology, just as does The Dante Quartet. (And note that the syphilis cells seen swimming around here are in an infected cornea – this is among other things a film of, around, and in the eye.) Unlike the films of Mary Ellen Bute or Larry Cuba, Comandon’s film is as representational and concrete as it gets – these are actual bacteria cells moving around in an actual body. But this could only be seen with a newly created micro-cinematographic camera, combining the motion picture with the microscope. The powerful magnification revealed an alien-seeming world that is all too real. The camera, meanwhile, not only made the motion of cells visible to the unassisted eye but preserved them for posterity.

Synchromy No. 2 (Mary Ellen Bute, 1936) 6 min

Bacteria—we can see that, thanks to Comandon. But what does it mean to see sound? Animator Mary Ellen Bute was one of the first female experimental filmmakers and a pioneer of visual music, in which an artist adopts musical concepts to develop visual ideas. Influenced by the ethereal light art of Thomas Wilfred, the playful animations of Oskar Fischinger, and the mathematical principles of composer Joseph Schillinger, Bute, working with her husband Theodore Nemeth, sought “to create MOODS THROUGH THE EYE as music creates MOODS THROUGH THE EAR,” as articulated in the titles to her early film, Synchromy No. 2. This film’s title likely refers to Synchromism, an early 20th century art movement originated by American painters Stanton Macdonald-Wright and Morgan Russell that sought to analogize color to music. Set to Wagner’s “The Evening Star,” Synchromy No. 2 finds Bute recording refracted and reflected light from glass jars, paper clips, rotating paper cut outs, and a statue of Venus, producing a dreamlike dance of otherwise inanimate objects.

Our Lady of the Sphere (Lawrence Jordan, 1969) 10 min projected in 35mm

Over a series of red, blue and green independent color planes, mythological and iconic creatures cut out from Victorian-era engravings and animated by Lawrence Jordan go about their surreal business. It’s difficult to explain what’s going on in this film in terms of who the characters are, or what their actions mean. What this film is “about” is a sense of rightness: every new shot is a surprise, and their cumulative effect is to create an entire coherent world, a world available nowhere else but this film.

Like Passage a l’Acte, Our Lady of the Sphere was created and originally exhibited entirely in 16mm. In recent decades, Lawrence Jordan had a “blow-up” 35mm print made, paid for by a British movie theater chain, and that is the format we’re showing tonight. 16mm film – economical, human-scaled, lending itself to individual creativity – has been the primary medium of much avant-garde filmmaking. Thus, avant-garde films were most often shown in 16mm-friendly venues: art galleries, underground DIY venues, and other less commercial spaces. When larger theatrical exhibition opportunities opened up for this kind of work, the 16mm-to-35mm blow-up print became an occasional boon to the avant-garde filmmaker.

Calculated Movements (Larry Cuba, 1985) 6.5 min

Some filmmakers found success in traversing mainstream and the experimental filmmaking terrain alike. An innovator in motion graphics, Larry Cuba worked with computer filmmaker John Whitney before being tapped by George Lucas to create the famous vector graphics of the Death Star Trench Run simulation for Star Wars (1977)—one of the first uses of CGI in a feature film and thus helping usher in a new era of computer filmmaking whose legacy can still be felt in today’s blockbusters.

Digital filmmaking has its own materiality—Cuba made Calculated Movements on a Datamax UV-1 personal computer, using the Z-grass graphics language. This raster-based system allowed Cuba to make images with solid volumes, rather than the individual dots of light he had employed in his earlier work. The resulting abstract film is filled with zig-zagging three-dimensional lines that pursue one another across the screen, punctuated by a percolating electronic score. Expanded cinema scholar Gene Youngblood said of the artist: “if there is a Bach of abstract animation it is Larry Cuba. Words like ‘elegant,’ ‘graceful,’ ‘exhilarating’ or ‘spectacular’ do not begin to articulate the evocative power of these sublime works characterized by cascading designs, startling shifts of perspective and the ineffable beauty of precise, mathematical structure. They are as close to music—particularly the mathematically transcendent music of Bach—as the moving-image arts will ever get.”

Abel & Associates Promo Reel (Robert Abel & Associates, 1974) 8 min

This sizzle reel of groundbreaking commercials and forward-thinking branding comes from the firm of Robert Abel & Associates. Even though they were made in 35mm, you wouldn’t have seen these spots at the movies—you’d have to see them at home on a small CRT television with limited resolution. This presentation allows us to take in their artistry at cinematic scale. Abel had worked with graphic designer Saul Bass and, like Larry Cuba, computer filmmaker John Whitney. Specializing in stop-motion photography and the development of innovative special effects, which included extensive use of 360-degree motion-controlled boom arms, optical printing, frontal and rear projection, and various early computer graphic systems, Abel brought an artist’s eye and a hipster’s sensibility to iconic campaigns for 7-Up, Kawasaki, Levi’s, Chevrolet, and countless other companies, as well as to VFX sequences for Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1980), Tron (1982), and the Jacksons’ music video for “Can You Feel It.”

Passage a l’Acte (Martin Arnold, 1989) 12 min

This film has always been a 16mm work and has never itself been in the large format – instead, it’s the source material that provides the large format. Passage a l’Acte (the title phrase comes from a psychology textbook and refers to impulsive behavior) consists entirely of imagery from a big-budget Hollywood production, in this case the Oscar-winning 1962 adaptation of To Kill a Mockingbird. Using a 16mm print of the Gregory Peck classic, Arnold reprinted the images one frame at a time, advancing forward in the action slightly, then backward to repeat. This labor-intensive editing technique results in looped motions and sounds, so that a family dinner scene that passes uneventfully in the original film becomes quite eventful here. Like Jean Comandon, Martin Arnold is magnifying imagery – only instead of a microscope, he’s using the optical film printer to magnify time and movement. An entirely different film is brought to the surface; a mesmerizing hyperfocus on small gestures and repetitive speech allows us to grasp the sexual repression, familial tension, and subtle gender and racial coding underlying Hollywood’s visual language.

Mirror (Matthias Müller and Christoph Girardet, 2003) 8 min projected in 35mm CinemaScope

Like Arnold, German filmmakers Matthias Müller and Christoph Girardet take oblique cues from Hollywood while also borrowing from mid-20th century European art cinema. In this double-screen CinemaScope projection, Müller and Girardet channel their obsessions with Alfred Hitchcock (seen in their 1999 found-footage taxonomy of the director’s visual fetishes in Phoenix Tapes), Michelangelo Antonioni, Alain Resnais, and David Lynch into this mysterious and haunting original short. The directors describe Mirror as “A woman, a man, guests at an evening party. Settings, which are gradually abandoned; the remains of an event, gazes that have lost their object.” The imagery speaks of isolation and actions not taken—figures are frozen between places and thoughts, leaving us with the mental space to make connections that may or may not be present.

Synchromy (Norman McLaren, 1971) 8 min

Can a film projector be a musical instrument? Maynard Collins has described Scottish-Canadian animator Norman McLaren’s use of the cinematic apparatus to meld sight and sound in Synchromy as one that eradicates “the psychic space between eye and ear.” The complex, candy-colored film employs McLaren’s proprietary method of synthetic sound production. McLaren created the soundtrack by photographing waveform images of his creation frame-by-frame onto the filmstrip’s optical soundtrack. When the film is projected, a light source shines through the soundtrack, and variations in light intensity are converted to soundwaves. What we hear in this film, however, is neither from recordings of natural sound events nor pieces of music capable of being performed by human musicians on conventional instruments. In other words, here is a score cannot be played by anyone or anything besides a film projector.

Once he was finished with the soundtrack for Synchromy, McLaren replicated the photographed soundtrack on the visual portion of the film; as a result, we experience a one-to-one correspondence between what is seen and what is heard. Near the end of the film, McLaren exhibits the full range of his animated sound techniques, as the viewer sees/hears simultaneity, harmony, and counterpoint, all in a dazzling display of linked sound and shifting color. The soundtrack emits clipped electronic notes arrayed in simple patterns of ascending or descending tones, which take on increasingly faster tempos. These patterns are punctuated with bursts of higher-pitched flurries of notes, and by its conclusion, they have exploded in hyperactive, polyphonic compositions of bass parts and melodic lines that become more layered, complex, and cacophonous, ringing out like slot-machine jackpots, tilting pinball machines, and fairground attractions.

Garden of Earthly Delights (Stan Brakhage, 1981) 3 min projected in 35mm

Once again, Stan Brakhage working directly on the filmstrip. Instead of painting, we have leaves, flowers, stems and other organic material collected by Brakhage from the yard in his Colorado mountain domicile and sandwiched between layers of 35mm splicing tape. One of us once had the chance to see Brakhage’s original of this film, with the actual plant material he’d pasted. Just as striking as the sight of the bulging sandwich of film was the unmistakable smell of vegetation as the reel was unbagged.

To understand the laborious nature of filmmaking like this, consider that the opening and closing sections of Garden were completed through a complex “bipack” printing process in the film lab. A color positive 35mm print was made of Brakhage’s original pasted plant work. This print was duplicated several times in photographic negative. The third generation of this negative print was then placed over the color print. This roughly 16-second section of the film is seen three times, each different due to printing at slightly varying exposures. In the final result, the plants have a luminous glow against a black background, as if the ground had become the night sky and the plants neon constellations in a continually vibrating cosmos.

Program notes 2025 Andy Ditzler and Gregory Zinman

Image: Film strip from The Dante Quartet (Stan Brakhage, 1987): Brakhage hand-painted these images onto 35mm film.

Courtesy of the Estate of Stan Brakhage and Fred Camper (www.fredcamper.com)

Thanks to Larry Cuba, Mark Toscano, Light Cone, Canyon Cinema, and everyone at the Plaza Theatre

Restored digital presentation of Robert Abel Promo Reel courtesy of the UCLA Film & Television Archive

Norman McLaren’s Synchromy is produced and distributed by National Film Board of Canada